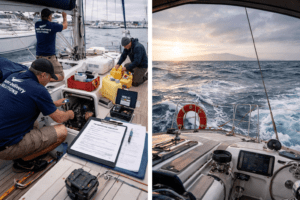

A Tasman Sea crossing from Queensland to New Zealand is not a casual offshore passage. It is a serious ocean delivery that exposes weaknesses in boats, crew, and planning very quickly. While yachts make the crossing successfully, most problems encountered offshore can be traced back to inadequate preparation, not bad luck.

This article sets out what actually matters when preparing to cross the Tasman from Australia to New Zealand, based on delivery realities rather than cruising optimism.

The Tasman Sea sits between two high-latitude weather systems and is dominated by fast-moving lows, strong frontal activity, and large, confused seas.  Unlike trade-wind routes, conditions are rarely stable for long.

Unlike trade-wind routes, conditions are rarely stable for long.

Key characteristics of the Tasman:

Rapidly changing weather

Steep sea states, especially in opposing wind/current

Limited bailout options once committed

High fatigue load on crew and systems

This is why insurers, brokers, and experienced delivery skippers treat the Tasman as a threshold passage. Boats and crews that are marginal are exposed quickly.

The Tasman will find movement. Anything that works loose offshore will do so repeatedly.

Before departure:

Inspect chainplates, deck fittings, pulpits, stanchions, and lifelines

Remove unnecessary deck gear and secure everything else

Eliminate water ingress paths—hatches, ports, cockpit lockers

Cosmetic issues are irrelevant. Structural ones are not.

Rig failure is one of the most common delivery-ending events.

Minimum expectations:

Standing rigging with known age and condition

No unresolved cracks, corrosion, or movement at terminals

Running rigging sized appropriately and not marginal

At least one genuinely heavy-weather sail option

A sail inventory designed only for coastal cruising is not adequate.

Engines are not backups on a Tasman crossing—they are primary safety systems.

Preparation should include:

Full engine service immediately prior to departure

Fuel system inspection (hoses, filters, tanks)

Spare filters, belts, impellers, fluids

Confidence the engine can run continuously if required

For power vessels, range calculations must assume head seas and reduced efficiency, not brochure numbers.

Autopilot failures are routine offshore. Steering failures are not rare.

At minimum:

Autopilot recently serviced and tested under load

Backup control options understood and usable

Emergency steering prepared and rehearsed

Crew fatigue skyrockets when steering systems are marginal.

Tasman crossings are long enough that single-point failures matter.

Critical systems:

Navigation (chartplotter + backup)

Communications (VHF + offshore comms)

Autopilot power supply

Battery charging and monitoring

Assume at least one system will fail. Plan accordingly.

New Zealand authorities and insurers expect offshore-standard safety equipment, regardless of flag state.

Core expectations include:

Liferaft in service

EPIRB and PLBs

Jacklines, tethers, and harnesses

Offshore first aid capability

Storm tactics appropriate to vessel type

Equipment that is “technically present” but untested is not adequate.

A Tasman crossing is not the place for a crew entirely new to offshore sailing.

At least one additional crew member beyond the skipper should have:

Night watch experience

Heavy-weather exposure

Basic mechanical competence

Personality matters offshore. Fatigue amplifies poor dynamics.

Expect disrupted sleep for extended periods.

Professional deliveries typically use:

Short, disciplined watch rotations

Clear rules around rest and decision-making

Conservative fatigue management

Poor watch systems lead directly to bad decisions.

Tasman crossings are frequently delayed mid-passage by weather or speed reduction.

Provisioning should assume:

Extra days at sea

Limited cooking ability in rough conditions

High caloric demand

Hydration redundancy

Running low on food or water offshore is not a planning error—it is a systems failure.

There is no fixed “best date” to cross the Tasman.

Instead, departures are built around:

Stable synoptic patterns

Manageable frontal spacing

Avoidance of strong opposing current/wind combinations

The most common failure mode is leaving too early.

Professional delivery schedules absorb waiting time. Rushed departures are a leading cause of aborted passages.

Queensland departure points vary, but common exits include Brisbane, Gold Coast, or further north depending on season and systems.

General routing logic:

Clear the coast cleanly

Avoid compressing into frontal boundaries

Set up to arrive NZ with manageable conditions

Landfall is often planned for Northland, including ports such as Opua or Whangārei, before repositioning south to Auckland.

Arrival timing matters. New Zealand coastal conditions can be severe even after a successful crossing.

New Zealand has strict arrival requirements.

Preparation should include:

Advance notice to authorities

Clean hull, anchor gear, and chain

Accurate documentation

Understanding of arrival port requirements

Failure here does not end at inconvenience—it can mean fines, delays, or forced haul-out.

Owners often underestimate the cumulative risk of this passage.

Professional delivery provides:

Conservative go/no-go decision-making

Structured preparation checklists

Crew accustomed to fatigue and weather stress

Clear accountability for outcomes

This is particularly relevant for:

Newly purchased vessels

Boats unfamiliar to the owner

Tight insurance or settlement timelines

Crossing the Tasman is not about bravado. It is about process discipline.

A Queensland–New Zealand crossing is achievable for many vessels—but only when preparation is honest.

If the plan relies on:

“It’s usually fine”

“We’ll sort it as we go”

“The boat’s done coastal miles without issue”

…then the plan is weak.

The Tasman rewards boats that are prepared conservatively and punishes those that are not.

Whether undertaken privately or via Yacht Delivery Solutions, the passage should be treated as what it is: a demanding offshore delivery that exposes shortcuts quickly.

Preparation is not an administrative step. It is the voyage.

WhatsApp us